You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘The Sign of the Four’ tag.

A business card from the Sherlock Holmes Museum on London’s Baker Street.

I suffered a major loss recently.

My phone died. It was not a smartphone by any sense of the word, and I did not use it to connect to the Internet. I used it for phone calls, texts, and the occasional picture.

It was not at all a well phone, and one morning it wouldn’t wake up. I tried applying phone CPR, desperately pressing buttons in the hope that I could revive it. “Stay with me, phone,” I pleaded. “STAY WITH ME!” Much to my relief, the phone turned back on. It worked for a few hours, as though it just wanted a chance to say goodbye, and then it shut down for good.

Now I have a smartphone.

That means I can now listen to podcasts on my phone while I take my morning walk. Today I streamed the latest episode of I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere, a podcast with charming and erudite hosts Scott Monty and Burt Wolder. The subject, of course, is Sherlock Holmes and everything associated with the great detective and his universe. The show I heard today was an interview with author Nicholas Utrechin. He has just published a book called The Complete Paget Portfolio, which reproduces every single illustration that the great Sidney Paget drew for the Holmes stories when they originally ran in the Strand magazine. I enjoyed the podcast immensely, and it got me musing about things Sherlockian.

I’ve been a Holmes fan for a long time now, and I can blame Soupy Sales. One night when I was around 12 or 13 I happened to catch What’s My Line, a TV show in which celebrity panelists sought to determine the occupation of a guest. The mystery guest that night was a man who worked for Abbey National, a bank whose headquarters occupied the address of Sherlock Holmes’s lodgings at 221B Baker Street in London. One of his duties was to respond to people who wrote letters to Sherlock Holmes.

During the course of the program, panelist Soupy Sales mentioned that Holmes used cocaine. This made me sit up and take notice. I hadn’t read any Holmes at that point, but I certainly knew who he was, and the idea that this fixture from popular culture might have used drugs surprised the heck out of me. It was like hearing that Tarzan had a drinking problem, or that Superman liked to kick Krypto the Superdog.

I set out to do a little research. On one of our bookshelves we had my grandfather’s copy of The Hound of the Baskervilles, a red-bound hardcover edition from the early 1900s. I pulled it down from the shelf and began reading. Like so many before me, and so many after, I was drawn immediately into the atmospheric setting of Victorian London, with hansom cabs and the clop-clop of horses’ hooves, and the mysterious bearded stranger following Dr. Mortimer through the streets. I could imagine the hushed tones of Dr. Mortimer’s voice when he said, “Mr. Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!” Above all, I was fascinated by the character of Holmes, who could learn so much from those little details that others overlooked, and his friendship with Dr. Watson, who was not the amusing dolt I had glimpsed in the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce movies on TV, but an intelligent, educated medical man.

I set out to do a little research. On one of our bookshelves we had my grandfather’s copy of The Hound of the Baskervilles, a red-bound hardcover edition from the early 1900s. I pulled it down from the shelf and began reading. Like so many before me, and so many after, I was drawn immediately into the atmospheric setting of Victorian London, with hansom cabs and the clop-clop of horses’ hooves, and the mysterious bearded stranger following Dr. Mortimer through the streets. I could imagine the hushed tones of Dr. Mortimer’s voice when he said, “Mr. Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!” Above all, I was fascinated by the character of Holmes, who could learn so much from those little details that others overlooked, and his friendship with Dr. Watson, who was not the amusing dolt I had glimpsed in the Basil Rathbone/Nigel Bruce movies on TV, but an intelligent, educated medical man.

There was one thing missing, though, in The Hound of the Baskervilles. There was not a single mention of cocaine. Soupy Sales must have been mistaken. But whether or not Holmes was addicted to cocaine, I was now hooked on Holmes. My middle-school library had a big omnibus edition of Holmes stories, so I checked that out and met for the first time people like Irene Adler (“To Sherlock Holmes she was always the woman), Jabez Wilson, Inspector Lestrade, Henry Baker, and the nefarious Professor Moriarty.

At some point I read The Sign of the Four. It began like this:

Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantel-piece and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case. With his long, white, nervous fingers he adjusted the delicate needle, and rolled back his left shirt-cuff. For some little time his eyes rested thoughtfully upon the sinewy forearm and wrist all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-marks. Finally he thrust the sharp point home, pressed down the tiny piston, and sank back into the velvet-lined arm-chair with a long sigh of satisfaction.

Three times a day for many months I had witnessed this performance, but custom had not reconciled my mind to it. On the contrary, from day to day I had become more irritable at the sight, and my conscience swelled nightly within me at the thought that I had lacked the courage to protest. Again and again I had registered a vow that I should deliver my soul upon the subject, but there was that in the cool, nonchalant air of my companion which made him the last man with whom one would care to take anything approaching to a liberty. His great powers, his masterly manner, and the experience which I had had of his many extraordinary qualities, all made me diffident and backward in crossing him.

Yet upon that afternoon, whether it was the Beaune which I had taken with my lunch, or the additional exasperation produced by the extreme deliberation of his manner, I suddenly felt that I could hold out no longer.

“Which is it to-day?” I asked,–“morphine or cocaine?”

Holy crap. Never again would I doubt Soupy Sales.

I wasn’t the only person intrigued by Holmes’s cocaine habit. Around the time that I discovered Holmes, Nicholas Meyer published The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, a novel in which the detective falls so deeply into addiction that Dr. Watson lures him to Vienna so Sigmund Freud can wean him off cocaine. The book was a huge best-seller and sparked a Holmes revival. I received a lot of Sherlockian books that Christmas. My grandmother got me The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. I also got The London of Sherlock Holmes, The World of Sherlock Holmes, In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes, The Sherlock Holmes Scrapbook, and Sherlock Holmes Detected. I got Naked Is the Best Disguise, in which, if I recall correctly, author Samuel Rosenberg postulated that “The Adventure of the Red-Headed League” was really a metaphor about anal rape. There was a lot about Nietzsche in it, too, and syphilis, other things that were perhaps a bit above the head of a 14-year-old. I think it helped me realize that literary criticism could be a bit silly.

At some point I received the big, two-volume Annotated Sherlock Holmes. One of my favorite Sherlockian gifts from this time was The Return of Moriarty by John Gardner. It told the story of Holmes’s great nemesis, who did not perish at Reichenbach Falls, but made a non-aggression pact with his adversary and later returned to London to resume his criminal enterprises. The book captured a real sense of Victorian London’s underbelly and it seemed as though yellow fogs should have been swirling through its pages.

I still have all those books, and many, many more. One of the first Holmes books I purchased myself was the Penguin paperback of The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. It cost $1.25, a bit pricey for me at the time, but worth it. On the cover was a photograph of a recreation of Holmes’s sitting room at 221B. (Years later I would see that same sitting room at the Sherlock Holmes, a pub in London.) I filled out my collection of the original stories with the Berkeley Books paperback editions, which also had pretty cool illustrations on the covers and cost a much more economical 60 cents.

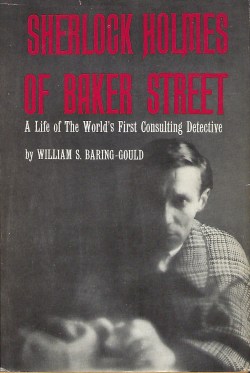

At this point in my life I have a big bookcase in my office filled with Holmes books. They have started to spill over into another bookcase, and I have filled a couple more shelves with books downstairs. I still have my grandfather’s old copy of the Hound, as well as one I picked up at a used bookstore in York, Pennsylvania, for $3.50 and discovered was a first American edition. I have a lot of pastiches, in which authors other than Conan Doyle try their hands at Holmes stories. Some are good, but many are not. I have books in which Holmes meets Dracula, Dr. Jekyll, the Phantom of the Opera, Harry Houdini, Theodore Roosevelt, Father Brown, Jack the Ripper, and the Martians from The War of the Worlds. I own several books about Holmes in the movies. I have a Sherlock Holmes cookbook, a Sherlock Holmes crossword book, and a Sherlock Holmes pop-up book. I have reference books like The Encyclopedia Sherlockiana, and several Sherlock Holmes biographies. My favorite biography is Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street by William S. Baring Gould, which I bought on a remainder table a long time ago for $2.49. I have books about Holmes’s London, as well as any number of collections of Sherlockian essays. As someone once said, “Never has so much been written by so many for so few.”

Over the decades my fascination with Holmes has ebbed and flowed, but it never goes away. I read something Sherlockian every now and then. I recently finished Mycroft Holmes, the novel co-written by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. While it is without a doubt the finest Sherlockian book ever written by an NBA superstar, it left me feeling underwhelmed. There was too much action, too many explosions, too much derring-do. It had the same flavor as the Robert Downey, Jr,. Holmes movies. They were entertaining enough, but it wasn’t the Sherlock Holmes I grew up with. On the other hand, I loved the BBC’s Sherlock, at least until it went off the rails in the last episode, and I also enjoy the CBS series Elementary. I am not a purist, but if you’re going to mess with the recipe at least come up with something interesting.

Purists might complain about the way Sherlock and Elementary place Holmes and Watson in the modern age, but that’s nothing new. Arthur Conan Doyle set one story, “His Last Bow,” on the brink of World War I. Until Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce starred in The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1939, film adaptations put Holmes and Watson in the modern world of telephones and automobiles instead of telegraphs and hansom cabs. After making two period films for Twentieth Century-Fox, the Rathbone/Bruce team abandoned the Victorian era to fight Nazis in the 1940s.

Holmes himself has evolved—or at least our perception of him has. Pastiche writers used to portray him as a superhuman thinking machine, but today’s interpreters often make him a victim of his own intelligence, a neurotic, broken genius who needs Watson to keep him grounded. That interpretation goes back at least to The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. (But Billy Wilder’s great and woefully overlooked 1970 film, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, also gave us a damaged detective.) Jeremy Brett’s Holmes on British TV in the 1980s became more and more neurotic as the series went on, possibly because Brett battled mental illness in real life.

I think Conan Doyle might have blanched at these interpretations. His Holmes was not superhuman but neither was he a sociopath. He wasn’t an unshaven slob like Robert Downey, Jr. or, to an extent, Elementary’s Jonny Lee Miller. (Conan Doyle’s Holmes had “a cat-like love of personal cleanliness”). He did use cocaine but eventually stopped. But the image of a man whose towering intellect raises barriers between himself and the rest of the world seems to strike a chord in our own neurotic, broken 21st century. That’s one of the great things about Holmes, I guess. He’s amazingly malleable to many ages and circumstances.

Neurotic and broken it may be, but at least the 21st century has podcasts like I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere. And phones as smart as Holmes with which to hear them.